Recently, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and National Marine Fisheries Service (collectively referred to as the “Services”) issued a final rule that amended federal interagency consultations under Section 7 of the Endangered Species Act (ESA). These updates may have significant impacts on projects; let’s delve into these changes to understand their implications.

What is Section 7 of the ESA? What are the ESA Section 7 regulation changes and what kinds of projects are likely to be most affected?

The purpose of the ESA is, in part, to provide a means whereby the ecosystems upon which endangered and threatened species depend may be conserved. Specifically, Section 7 requires federal agencies to ensure that their actions are not likely to jeopardize the continued existence of any endangered or threatened species or result in the destruction or adverse modification of designated critical habitats. Section 7 and its implementing regulations describe how federal agencies and their applicants, in coordination with the Services, achieve the conservation purposes of the ESA.

Now effective, three key changes to the regulations implementing ESA Section 7 are as follows:

- The definition of the environmental baseline as applied to ongoing federal actions.

- The definition of effects of the action with respect to interpretation of the “reasonably certain to occur” standard.

- The interpretation of the conservation standard applicable to Section 7 and new considerations for compensatory mitigation.

Projects most likely to be affected by these recent ESA Section 7 regulation changes include those that have some form of federal involvement through one or more federal land management agencies (like when crossing lands managed by the Bureau of Land Management or the U.S. Forest Service), are supported by federal funds or loan guarantees (like programs through the U.S. Department of Energy), or require permits or approvals from regulatory agencies (like the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission or the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers). Many linear infrastructure projects (transmission lines, pipelines, roads) and water management projects (reservoirs, dams, canal systems) have involvement by one or more federal agencies.

Southwestern willow flycatcher nestlings in nest, Key Pittman Wildlife Management Area, Nevada

Southwestern willow flycatcher nestlings in nest, Key Pittman Wildlife Management Area, NevadaHow might the scope of biological assessments change and how might this complicate completion of these assessments?

Biological assessments are analysis documents prepared by federal action agencies when their activities may affect one or more listed species or critical habitat areas. Often, project proponents draft a biological assessment on behalf of a federal agency, which then reviews and ensures that the content meets their expectations. Then federal agencies share their biological assessments with the Services to initiate the consultation process. Getting the scope of analysis right in a biological assessment is often challenging.

The first two key ESA Section 7 regulation changes may have a significant impact on the scope and complexity of analysis for biological assessments.

Redefining environmental baseline

Close up of an American Burying Beetle on a Presence/Absence Survey

Close up of an American Burying Beetle on a Presence/Absence SurveyThe environmental baseline describes the condition of listed species or critical habitats in the action area (the area where effects of the action occur) in the absence of the proposed federal action. The Services consider the environmental baseline when evaluating if the effects of the proposed action would likely jeopardize the survival and recovery of the species or destroy or adversely modify critical habitat in ways that are not permissible under the ESA. Importantly, the condition of the environmental baseline is described in a biological assessment but is not an effect of the action that influences the level of consultation needed to satisfy ESA Section 7.

Under the new regulations, the Services established that the consequences of ongoing activities are part of the environmental baseline only when a federal agency lacks the discretion to modify the ongoing activity. When an agency is proposing to modify a discretionary ongoing activity, the effects of the action include consideration of the ongoing activity as a whole, not just changes to the ongoing activity.

The change reopens analysis of the full scope of the ongoing activity, which could expand the boundaries of the action area, expand the list of resources that are evaluated, increase the level of effect determination, and result in greater assessment of incidental take — even if the proposed change to the ongoing activity is itself minor.

Redefining the reasonably certain to occur standard

The reasonably certain to occur standard of foreseeability applies to both the scope of effects that warrant analysis in a biological assessment and the amount of incidental take (typically, the number of animals of a threatened or endangered species that would be killed, wounded, or harmed) expected from those effects. The intent of this standard is to ensure that regulatory compliance is based on evidence that is more than speculation or conjecture.

Under the new ESA Section 7 regulations, the Services removed language that explained the reasonably certain to occur standard as being equivalent to having “clear and substantial information” that an effect would occur, even if the outcome was not absolutely certain. Instead, the Services offered non-regulatory guidance in the final rule that related this standard to the use of best available scientific and commercial information in its analyses. The Services also indicated that they intend to provide additional policy guidance in the form of a revised consultation handbook.

This change is important because the best available information is not always sufficient to answer questions about which potential effects to threatened or endangered species are reasonably certain to occur. With a lower threshold for establishing which effects are reasonably certain to occur, the scope of analysis in a biological assessment could expand to include effects that are more speculative and increase the size of action areas, the number of species considered, the complexity of cumulative effects analyses, and the amounts of incidental take.

A northern long-eared bat is banded to identify the individual as it migrates across the landscape from year to year

A northern long-eared bat is banded to identify the individual as it migrates across the landscape from year to yearWhen might compensatory mitigation be required, and how might these new obligations complicate the delivery of projects with federal involvement?

The new compensatory mitigation provision in ESA Section 7 upends decades of prior practice and regulatory interpretation and may add cost, time, and complexity to the consultation process.

Compensatory mitigation as a reasonable and prudent measure

The Services define “compensatory mitigation” as actions that offset any adverse impacts that remain after implementing measures that first avoid or minimize the amount or severity of those impacts. Compensatory mitigation measures in the context of the ESA often include actions that protect and enhance, restore, or manage habitat for threatened or endangered species in a way that provides a conservation “uplift” or benefit over the existing contribution of the habitat toward the status of the species.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) issued detailed policy guidance in 2023 establishing performance standards and other criteria for effective and durable compensatory mitigation projects.

A completely new take on compensatory mitigation

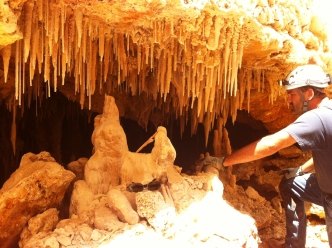

Cave encounter during construction of a subdivision in Williamson County, TX. Potential endangered species issues were already covered in the county’s Regional Habitat Conservation Plan.

Cave encounter during construction of a subdivision in Williamson County, TX. Potential endangered species issues were already covered in the county’s Regional Habitat Conservation Plan.In a significant departure from past practice, the Services changed their decades-long interpretation of the type of conservation actions needed to obtain incidental take authorization for projects with federal involvement. Previously, the Services unequivocally asserted that compensatory mitigation was not required and that only reasonable and prudent measures to avoid or minimize the amount of anticipated incidental take, through no more than minor modifications of the project, were necessary.

Under the new ESA Section 7 regulations, the Services establish a new interpretation that “minimize the impact of take” can include actions that offset impacts (provide compensatory mitigation) when necessary or appropriate to conserve listed wildlife. Since compensatory mitigation is not part of the project itself, the Services now consider compensatory mitigation to be consistent with their ability to prescribe mandatory reasonable and prudent measures to minimize the impact of take.

Importantly, the Services reserve the ability to determine when compensatory mitigation is necessary or appropriate, as well as the form and amount of mitigation.

The challenges that the compensatory mitigation updates may bring

Consistent with the 2023 USFWS policy on compensatory mitigation, the Services indicate that they may expect mitigation to be in place before an action is taken. Conservation banks offer pre-established credits that can be purchased for compensatory mitigation, but most listed species are not addressed by these market-based conservation programs or conservation credits are not available in the right amount or location to be applicable to the impact.

The new USFWS compensatory mitigation policy establishes high standards for conservation actions that may qualify as compensatory mitigation to improve the likelihood that the conservation benefits will be achieved. While these high standards will likely improve the quality of compensatory mitigation, they likely will also make it more difficult and costly to bring new conservation projects to market. This challenge may drive short-term scarcity and increased long-term costs. It will take some time for the compensatory mitigation market to catch up with new demand established by the regulation changes.

It is likely that the addition of compensatory mitigation to the ESA Section 7 process will be challenged in court. Legal challenges will extend the period of uncertainty about whether and how compensatory mitigation may be applied to projects with federal involvement.

The discretionary ability for the Services to require (or not) a particular amount, form, and timing of mitigation will also generate uncertainty as this regulation is applied across different regions and offices, for different species, and for different types of projects. At present, it is unclear how much variation to expect when planning and delivering projects.

Seining for the threatened and endangered Rio Grande Silvery Minnow, waders

Seining for the threatened and endangered Rio Grande Silvery Minnow, wadersMinimize project delivery risk with SWCA

SWCA can help reduce the impact of these ESA Section 7 changes on project timelines and budgets in several ways.

First and foremost, SWCA uses sound science to help determine whether effects are reasonably certain to occur. Detailed applied science on specific threatened or endangered species is often lacking but can be extremely helpful for countering generalities in the scientific literature. Consider if investing in species-specific science might be appropriate for your organization to help pave the way for better consultation outcomes. SWCA employs experts on a wide range of animal and plant species, experts in study design and statistical analysis, and experts in emerging technology and tools to collect and process field data. We can help identify areas where targeted scientific inquiry may be influential for advancing important projects or programs.

SWCA can also help you consider the potential impacts of your overall project portfolio or program to identify future needs for compensatory mitigation and ways to help ensure that offsets are available when you need them. Our ecological restoration and land services groups are skilled in identifying landowner partners and developing and implementing strategies for generating conservation uplifts.

Our ESA regulatory experts are working on a wide variety of projects with agency representatives across the country and at all levels of government. Our collective experience and contacts can help you understand emerging best practices and expectations for regulatory compliance under these and other rule and policy changes. We can help you develop a compliance approach that best meets your business needs and advances the conservation of threatened or endangered species.

Meet the Expert

Amanda Glen, Senior Natural Resources Technical Director, Biological Services

With more than 25 years of consulting experience specializing in the Endangered Species Act (ESA), Amanda Glen provides strategic guidance to clients on permitting and compliance for matters involving protected wildlife, plants, and habitats. View bio.