An afternoon thunderstorm rolls across the plains of northern Texas and on the banks of the Red River, the former cattle pastures and agricultural fields at Riverby Ranch slowly begin to fill with water. But there is no cause for concern; in fact, everything is going according to plan. As the North Texas Municipal Water District (NTMWD) creates the area’s first major reservoir in nearly 30 years only a few miles from the Ranch, SWCA’s stream and wetland restoration plans will offset habitat lost to the new lake’s rising waters with a flood of its own – creating protected waterways and wetlands where cattle once grazed.

Bois d’Arc Lake

About seven miles upstream of the Ranch, Bois d’Arc Lake is taking shape. Once filled, the 16,641-acre lake will provide a critical supply of drinking water for two million people in north Texas, helping meet the demands of the area’s growing population.

In addition to the much-needed drinking water, Bois d’Arc Lake will also provide a variety of recreational opportunities for residents and visitors flocking to the area. Fannin County expects to see hundreds of millions of dollars in new economic activity each year between the construction of waterfront homes and associated property taxes, hotel occupancy taxes, visitor spending, and 2,400 new long-term jobs in the area.

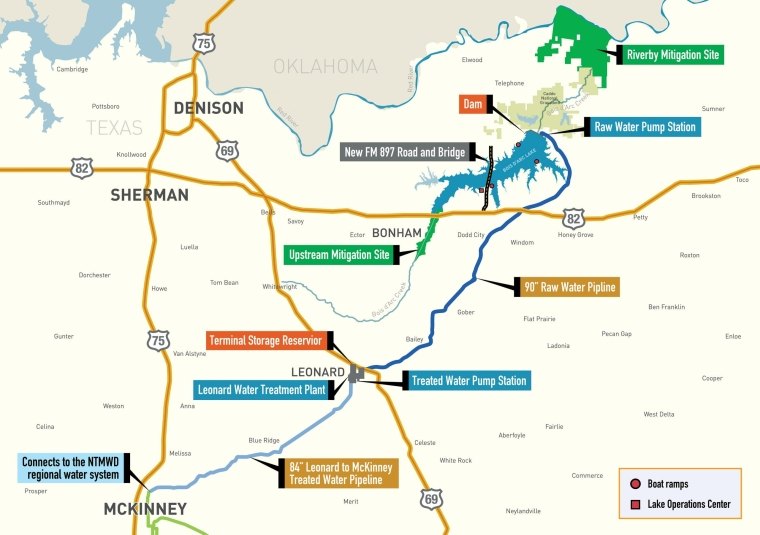

As one can expect for something of this scale, this new lake has been a long time coming. Planning and permitting for the project began in 2003. Riverby Ranch, the 15,000-acre mitigation area and location of SWCA-designed streams and wetlands, was purchased in 2010. Construction of the dam on Bois d’Arc Creek and water treatment plant began in 2018, followed by boat ramps, recreational facilities, and six miles of new road, including a 1.3-mile bridge bisecting the lake. New pipelines were also needed to move raw water to the treatment plant in nearby Leonard, Texas, and treated water further southwest to McKinney, Texas, where it will connect to NTMWD’s 610+ mile water supply network that serves two million people in about 80 communities across 10 Texas counties.

Map courtesy of NTMWD

Map courtesy of NTMWD

Mitigation at Riverby Ranch

Under Section 404 of the Clean Water Act, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) led an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for this project and approved a mitigation plan to address any unavoidable environmental impacts. For example, during construction, some areas of timber were left at the lake site to become submerged aquatic habitat while other portions were removed. NTMWD needed to mitigate, or offset, impacts like this habitat loss by creating new habitat or improving existing environments in another location. Freese and Nichols, Inc. provided an original mitigation plan in January 2017, which NTMWD was required to implement.

NTMWD purchased Riverby Ranch and the Upper Bois d’Arc Creek Mitigation Site upstream of Bois d’Arc Lake to mitigate the unavoidable impacts associated with the lake. The mitigation plan includes planting more than five million trees and restoring or enhancing 8,500 acres of wetlands and 69 miles of stream channels. Once completed, this will be one of the largest approved mitigation efforts in the U.S. for a single permitted project.

Resource Environmental Solutions (RES), the nation’s largest ecological restoration company and turn-key providers for the mitigation project, brought SWCA on board to design the stream and wetland restoration components of the comprehensive Permittee Responsible Mitigation (PRM) project. SWCA also worked with several subconsultants on the design plan including Five Smooth Stones Restoration, Tailwater Limited, Green Water Restoration, and Simple Design Solutions, LLC. It can often take decades for the environmental improvements at a mitigation site to become self-sustaining, so RES will monitor and maintain the site for the next 20 years or until all the regulatory mitigation requirements are met, whichever comes first.

Stream Channel Design

From the 1800s, farmers and ranchers in the area straightened, channelized, or relocated many of the stream channels at Riverby Ranch to improve drainage. Farmers dug ditches to drain some of the naturally occurring wetlands to create more suitable farmland on the property. This human intervention resulted in much shorter streams that became disconnected from their historic floodplains over time and downcut, where erosion cuts a deeper and narrower path into the stream’s active channel, often causing stream banks to fail.

To improve the condition of approximately 70 miles of stream channels on the property, SWCA’s restoration designs focused on two main options as required by NTMWD’s mitigation plan: 1) enhance and protect existing stream channels that were still in manageable condition, or 2) restore highly degraded streams and their connection to adjacent floodplains and wetlands, with particular focus on the streams’ cross-sectional dimensions, aerial patterns, and longitudinal profiles.

Stream Enhancement

Of the two options, enhancing existing streams is a relatively straightforward process. Planting native grasses and trees along the banks help stabilize and protect the streams from further erosion. Dense vegetation in the riparian zone can slow down rushing waters during a runoff event. Plant roots help lock the soil into place, keeping it from eroding into the water and washing downstream. Vegetation also regulates stream water temperature which is important for fish and aquatic habitats.

Stream Restoration

Stream restoration, on the other hand, is more complex. The dimension, pattern, and profile of any particular stream, known as its form, is a result of all streams’ natural tendency to move water and sediments that enter the system most efficiently. The most efficient form always includes a connection of the stream channel to a nominally wide floodplain at the bankfull discharge, which is also known as the channel-forming, effective, or dominant discharge. Stable streams have a form that neither degrades nor aggrades and is in dynamic equilibrium with the contributing watershed water and sediment loads.

Once a stream or its watershed is altered, the dynamic equilibrium is disturbed and the channel will enter a channel evolution process to establish a new stable form at a lower elevation, including the development of a new, entrenched geomorphic floodplain connected to the new, lower channel at bankfull discharge. Although this channel evolution process results in a new stable channel, the downcutting process results in a disconnection from the original floodplain and a lowering of the groundwater table. Both results have a significant negative impact on the historic wetlands that were part of the original floodplain.

As such, when restoring an ecosystem at watershed-scale, including streams, floodplains, and wetlands, the preferred stream restoration approach is to raise the degraded, downcut stream back up to the original floodplain. This is done by designing and constructing a new stream adjacent to the original stream that has the proper dimension, pattern, profile, and connection to the original upper floodplain. This is referred to as Priority I stream restoration.

Willow Branch Existing Condition with Downcut Banks (January 2019)

Willow Branch Existing Condition with Downcut Banks (January 2019)

If a stream on Riverby Ranch was too degraded to prevent the channel evolution process or was already downcut from the original floodplain, SWCA designed a Priority I stream restoration plan. Once construction is complete, water flow is diverted into the new channel and crews fill in the old stream with excavated dirt or section it off into small oxbow ponds to store excess water and recharge groundwater in drier months. The gradual slope and stream structures of new channels slow down water flow, which decelerates the degradation process and promotes growth of vegetation.

Willow Branch, the largest designed channel on the property, is an excellent example. As seen in the aerial photo, the newly constructed channel lies to the left of the degraded channel. The team turned the degraded channel into a series of open-water ponds by installing multiple plugs; these ponds now serve as additional aquatic habitat next to the newly restored channel. This restoration will provide frequent floodwaters and a very shallow groundwater table to help restore the wetlands on the floodplain. Since the restored stream is stable and in dynamic equilibrium, it will not degrade or aggrade. Therefore, SWCA, along with RES and Wright Contracting, LLC crews, was able to restore in-channel aquatic habitat features consisting of riffles and pools, woody debris, and aquatic and bankside vegetation without the fear that they will be destroyed in the channel evolution process.

Willow Branch During Construction (June 2020)

Willow Branch During Construction (June 2020)  Willow Branch Three Months After Construction (September 2020)

Willow Branch Three Months After Construction (September 2020)

Wetland Design

Creating wetlands is another important mitigation technique at work at Riverby Ranch. SWCA’s design plan for this area consisted of forested wetlands and emergent wetlands. Here, forested wetlands use terraced berms to collect and trap rainfall in areas growing mostly with trees. One way to create emergent wetlands is for crews to construct large depressions in the ground to collect rainfall as well as water flowing down nearby slopes or from natural springs. Emergent wetlands typically have herbaceous plants like grasses or reeds that live near the water’s edge.

Wetland Berm Holding Water (October 2019)

Wetland Berm Holding Water (October 2019)

On average, areas of north Texas receive about 36 inches of rainfall each year. So, rain is not the issue, the water simply needs a little gentle persuasion on where to go once it lands. The berms RES has constructed are ridges up to two feet tall and made of fill dirt, with strategically placed outlet structures that help restrict drainage. By building them to cross slopes on the topography, precipitation falling upslope of the berm is slowed down as it flows across the landscape. This helps water infiltrate into the soil, and native vegetation establish and grow, restoring the former pastures of Riverby Ranch back to wetlands. The team also restored the historic topographic landscape of these wetland areas by constructing hundreds of shallow macro depressions that fill like a puddle in a backyard, retaining water for wildlife for longer periods during the dry season.

A Legacy for Future Generations

Future generation visiting Riverby Ranch. (Photo courtesy of RES)From the first permanent settlements of hunter-gatherers to the megacities they later spawned, humans have always shaped our world to meet our growing needs, and projects like this are no exception. Only in our recent history, however, have we had the forethought, and legislative encouragement, to offset our environmental impacts with watershed-scale ecological restoration projects. Where one tree is removed, another puts down roots. Where a stream is dammed and a grassland or forest inundated, thousands of acres of new habitat are carefully constructed, maintained, and permanently protected in its stead. Future generations will have the opportunity to enjoy these natural landscapes and healthy ecosystems, and thanks to this forward-thinking balancing act between NTMWD’s Bois d’Arc Lake and Mitigation Project, millions of people in North Texas will be able to put down their own roots and have the water they need to grow.

Future generation visiting Riverby Ranch. (Photo courtesy of RES)From the first permanent settlements of hunter-gatherers to the megacities they later spawned, humans have always shaped our world to meet our growing needs, and projects like this are no exception. Only in our recent history, however, have we had the forethought, and legislative encouragement, to offset our environmental impacts with watershed-scale ecological restoration projects. Where one tree is removed, another puts down roots. Where a stream is dammed and a grassland or forest inundated, thousands of acres of new habitat are carefully constructed, maintained, and permanently protected in its stead. Future generations will have the opportunity to enjoy these natural landscapes and healthy ecosystems, and thanks to this forward-thinking balancing act between NTMWD’s Bois d’Arc Lake and Mitigation Project, millions of people in North Texas will be able to put down their own roots and have the water they need to grow.

Read more from The Wire, Vol. 22, No. 1 below: