Environmental conflicts are among the most challenging of public policy disputes. A complex set of differing interests and many stakeholders complicate decision-making and project implementation. Such disputes may arise in regional or national policy debates, during planning and permitting of specific projects, or when facing site specific compliance and enforcement issues.

ENVIRONMENTAL CONFLICT RESOLUTION (ECR) is a systematic approach to untangle environmental conflict by:

- The deliberate framing of issues

- Involvement of all affected stakeholders

- Collaborative problem-solving using interest-based (as opposed to positional) negotiation.

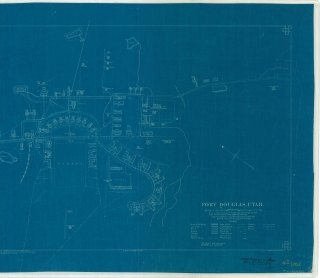

To illustrate how ECR can benefit a project, consider Historic Fort Douglas in Utah. In the spring of 2015, Fort Douglas National Historic Landmark in Salt Lake City was undergoing construction to modernize an aging electrical utility system. During that construction, crews encountered buried structural remains of the fort’s earliest days. SWCA used the ECR framework to address the ensuing environmental conflict.

HISTORY OF FORT DOUGLAS

Fort Douglas represents the entirety of Utah’s civil war era military history. Established as a frontier fort by the Union army in 1862 to protect the overland mail route, Fort Douglas was positioned on the benches of Utah’s Wasatch Mountains overlooking the growing Mormon settlement in the Salt Lake Valley. A company of volunteer soldiers from California and Nevada arrived in October and built semi-subterranean “dugouts”—some lined with unfired adobe bricks—to provide shelter during the first winter. Construction of permanent barracks began the following spring along what was later named Potter Street.

The fort played a surprisingly central role in the nation’s military history given its relatively small size. For a brief time in 1898, Fort Douglas housed a company of the famed Buffalo Soldiers from the 24th Infantry Regiment. During World War I and again in World War II, the installation served as an army induction center and training garrison, as well as a prisoner of war camp. Fort Douglas assumed the logistics functions of the Ninth Service Command, moving those duties away from the Presidio on the California coast. Following World War II, once the Ninth Service Command was returned to San Francisco, activity at Fort Douglas diminished and the fort was placed on closure status in 1975.

The National Register of Historic Places was established in 1966 as a registry of locations across the nation that embody and represent important historical events, historical figures, unique or historically important architectural styles, or locations where important information needed to further historical research are found. In June of 1970, the National Park Service and the Keeper of the Register determined that Fort Douglas was historically significant and much of the fort was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Localities listed on the National Register of Historic Places can be historically important at local, regional, or national scales. National Historic Landmarks, however, are limited to those locations that are of national historic significance. Fort Douglas was granted National Historic Landmark status in May 1975.

REPURPOSING A LANDMARK

Military activity at Fort Douglas declined after World War II and the Department of the Army placed the fort on closure status in 1975. Its eventual closure did not occur, however, until it caught the attention of the congressional Base Realignment and Closure Committee in the late 1980s. As part of the National Defense Authorization Act of 1991 (Public Law 101-510), the Department of the Army closed most of Fort Douglas and transferred its ownership of the closed fort to the University of Utah. As part of this transfer, the University of Utah agreed to assume responsibility for maintaining the historic character of Fort Douglas as a National Historic Landmark.

When Salt Lake City was selected to host the 2002 Olympic Winter Games, the Salt Lake Olympic Organizing Committee was immediately tasked with finding appropriate venues for the games.

Ice rinks, luge tracks, ski jump hills, and a speed-skating oval all needed to be built. As did the Olympic Village to house athletes from 78 participating nations. Student housing at the University of Utah at that moment was aged and insufficient for anticipated growth of the university. With its new acquisition of land there was a unique opportunity. New student housing could be built at the University of Utah and its timing could be tied with the 2002 Salt Lake games.

Today, Fort Douglas on the University of Utah campus provides not only housing but is also home to a hotel/conference center, restaurants, and academic departments. Historic Fort Douglas has been fully integrated into the University of Utah. Yet, beneath this vibrant university community lies an aging utility network in need of modernization.

HISTORY UNDERGROUND

One thing about dirt is that you can never be completely certain what lies beneath until you move it. Sometimes the turn of a shovel can be a surprise, and sometimes those surprises aren’t pleasant. Such was the case at Fort Douglas when, on a cold February morning a meeting was convened with more than 20 people, representing the University of Utah, the Utah State Historic Preservation Office, the National Park Service, the Fort Douglas Military History Museum, the State of Utah and Salt Lake City among others.

Historic maps had not been examined. Historic preservation agencies had not been consulted. But excavation of a construction trench had proceeded. Archaeological features had been uncovered and historic artifacts—including a Civil War-era bugle insignia pin—had been found inside the construction trench. History had been damaged and nobody participating in that meeting was happy.

During construction to upgrade subsurface utility lines, crews inadvertently uncovered previously unknown and undocumented structural remains of historic Fort Douglas. Construction activity damaged historic remains in one location and uncovered but did not damage historic remains in another.

To complicate things further, completion of the planned electrical utility improvement project would involve additional construction activity in undisturbed areas with a high likelihood for containing undocumented historic remains. The University of Utah, as owner and steward of historic Fort Douglas, needed to develop a preservation plan, and this plan needed the involvement and input of those at that February meeting. All the parties needed to collaborate and needed to work through the conflict that had been presented.

USING THE ECR FRAMEWORK

The ECR framework provides an effective way to confront conflicts like the discovery at Fort Douglas with complex issues and many stakeholders with differing interests. ECR relies on a few fundamental principles: carefully framing and detailing the exact issues that need to be addressed, ensuring that all of the parties who have a genuine stake in the issues have an opportunity to participate, and then engaging those parties in interest-based negotiation to find solutions to those issues. For the Potter Street discovery at Fort Douglas, the University of Utah asked SWCA’s experienced ECR practitioners to facilitate its resolution.

At Fort Douglas, we found the primary issues to be addressed involved mitigating damage to the newly discovered historic features and minimizing the potential for additional impacts while facilitating completion of the needed infrastructure improvement project. Importantly, the University of Utah, the Utah State Historic Preservation Officer, and the National Park Service Historic Landmarks Program all needed to agree to the measures decided.

At that first meeting in February, and in those that followed, SWCA’s facilitator led workshop discussions to identify each party’s underlying interests at Fort Douglas. From these interests, the parties were then led through a series of facilitated discussions to conjure a wide range of alternative measures that might be taken to address each issue. Once a comprehensive list of options was developed, SWCA facilitated discussions among the stakeholders to evaluate each alternative and ultimately select those alternatives that best met everyone’s interests.

RESOLUTION ACHIEVED

Over the course of two face-to-face workshops, SWCA’s facilitated conversations between stakeholders resulted in development and execution of a Memorandum of Agreement that addressed key issues of disagreement. The agreement developed detailed actions necessary to mitigate the impacts that had occurred to historic remains, minimize impacts to those historic features that were exposed but not impacted, and processes to avoid additional impacts as the infrastructure improvement project was completed.

At that initial meeting, it was hard to envision that all the stakeholders would come to agreement, but that’s exactly what happened in the end. Following the ECR protocol provided a map and framework for achieving resolution. The time investment up front – meeting face-to-face, collaborating – saved time and headaches in the long run and resulted in the best outcome for the project.

For more information about our Environmental Conflict Resolution services, contact Kelly Beck at kbeck [at] swca [dot] com (kbeck[at]swca[dot]com).